Anti UPX

Description:

A simple packed binary? Think again! This executable claims to be UPX-packed, but something isn’t quite right. Standard UPX tools fail to unpack it, perhaps trying to unpack manually able to reveal the flag.

- Category: Reverse

- Flag format: FLAG{[a-zA-Z0-9]+}

Solution:

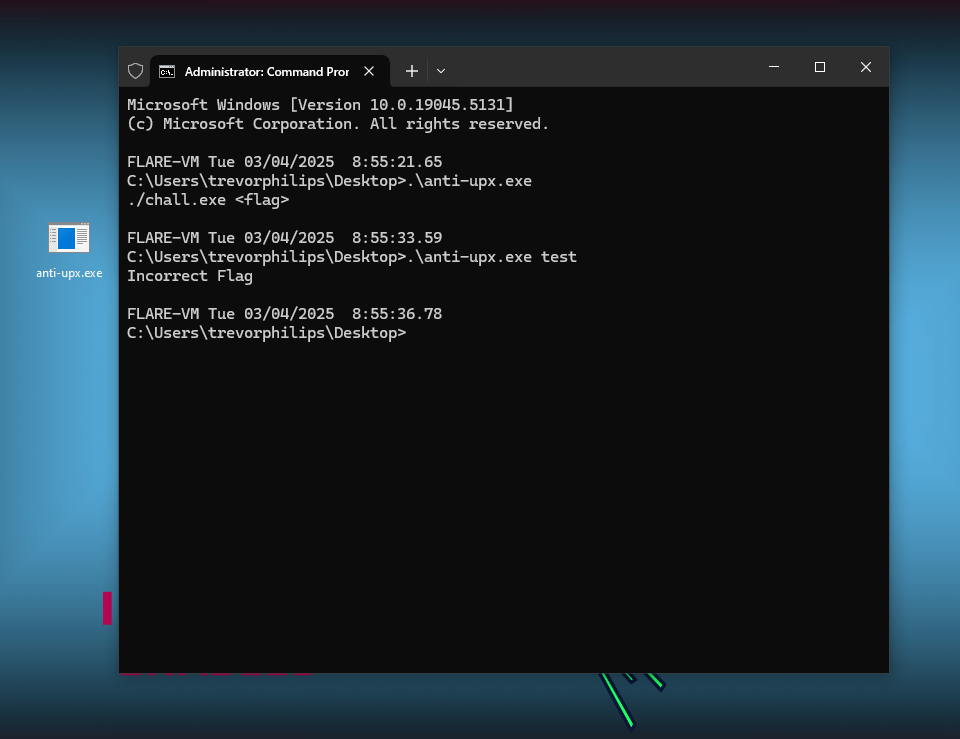

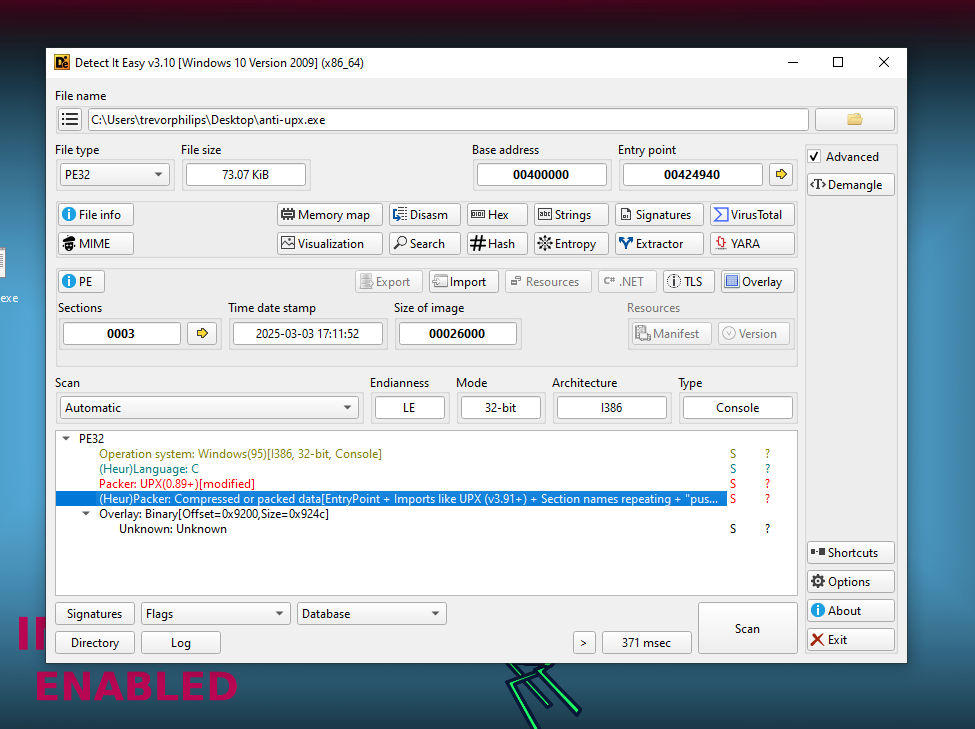

The executable accepts a flag string as arguments. Before decompiling with IDA, run DIE to understand static properties of the executable.

From the output, we notice is packed with UPX. Trying to unpack with upx will return error as the section header is corrupted.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

C:\Users\trevorphilips\Desktop

λ upx -d anti-upx.exe

Ultimate Packer for eXecutables

Copyright (C) 1996 - 2024

UPX 4.2.4 Markus Oberhumer, Laszlo Molnar & John Reiser May 9th 2024

File size Ratio Format Name

-------------------- ------ ----------- -----------

upx: anti-upx.exe: CantUnpackException: file is modified/hacked/protected; take care!!!

Unpacked 0 files.

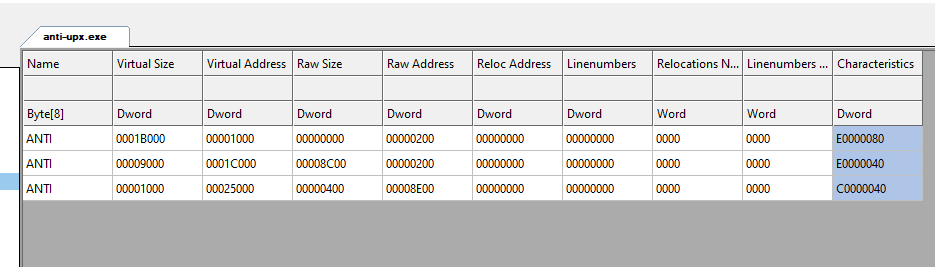

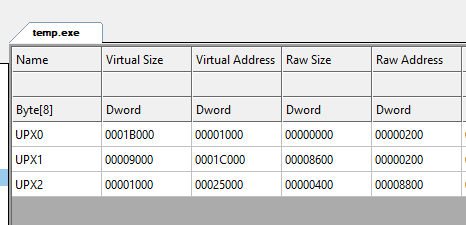

Use CFF Explorer to check the section headers.

Normally, UPX packed binary will have UPX with indexed as magic number for marking the section header. Here is an example of a uncorrupted UPX packed section header.

UPX will only unpack the executable if the section headers contain the standard UPX section names for identification purposes:

UPX0: Containing compressed.textsectionUPX1: Rest of the paced data (.data,.rdata,etc)UPX2: Is optional, appears for extra section if contain from the original unpacked executable

Next, we have to dump the unpacked binary from memory when debugging it with x32dbg along with OllydumpEx and Scylla.

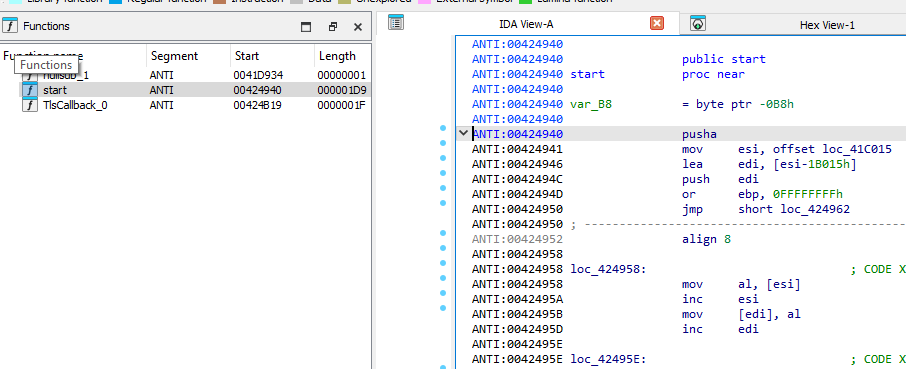

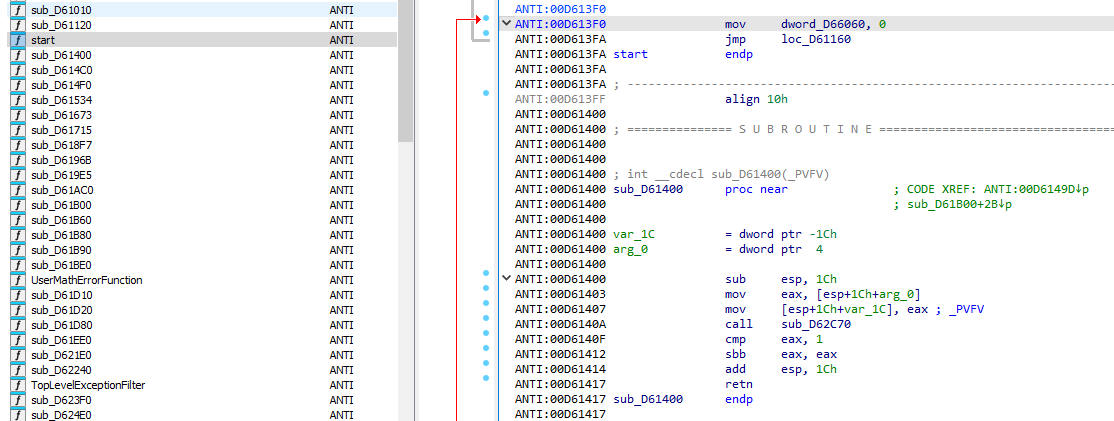

Before proceeding, lets try to see the function names contains at the packed executable in IDA.

Here we can see the function start at (0x00424940, also similar to the output of DIE indicating the entry point), which serves as the main entry point for execution. Since this binary was originally UPX-packed but has had its section headers modified to “ANTI”, this makes standard UPX unpacking to fail.

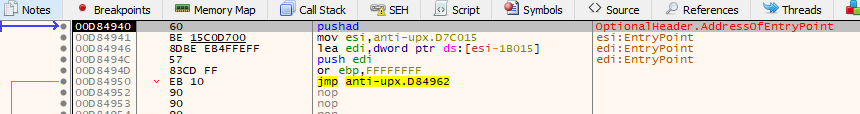

Load it into x32dbg, the first breakpoint it will hit at the module ntdll.dll. Hit run again will bring into the entry point of the executable.

If comparing IDA and x32dbg side by side, notice that assembly instruction used for UPX entryp point is pushad. It uses pushad to preserve register states during unpacking the stub. After unpacking, it will continue with popad and a jmp or call to transfer control to the Original Entry Point (OEP) of the unpacked binary.

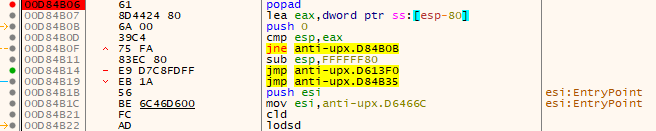

Next, use Find Command function to search for popad instruction and set a breakpoint there.

Now, it has completed unpacking process, the next instruction will be jmp to transfer execution to the OEP. To summarize the UPX unpacking process:

pushad- storing registers onto the stack for unpacking process- unpacking process starts by decompress the packed sections into the memory

popad- restore back the registersjmp OEP- redirects instruction execution

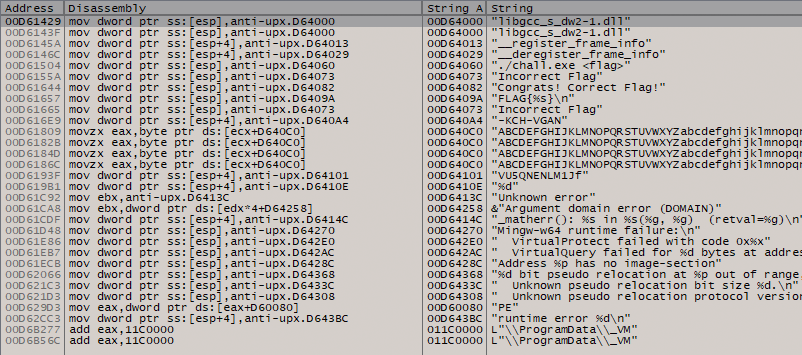

Now, we can step into the jmp instruction, with using search strings function within the current module, we able to see strings that is used to prompt in the beginning of running test input.

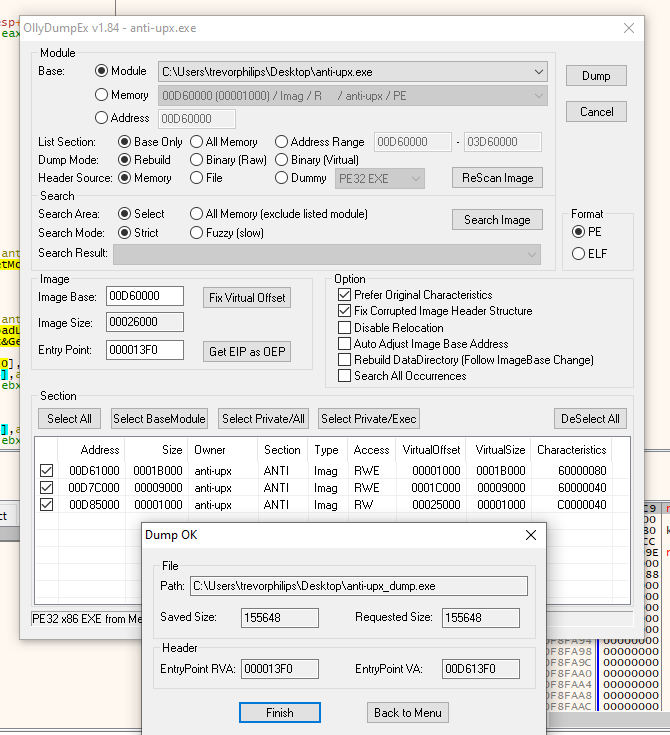

Next, dump the process using OllyDump. Here are the steps:

- Get EIP as OEP

- Click Dump

However, the image base and entry point of the dump is followed by the UPX packed allocation. This dump will be used as reference when decompiling with IDA, not for executing it. Next up, using Scylla to build to Import Address Table for the dump.

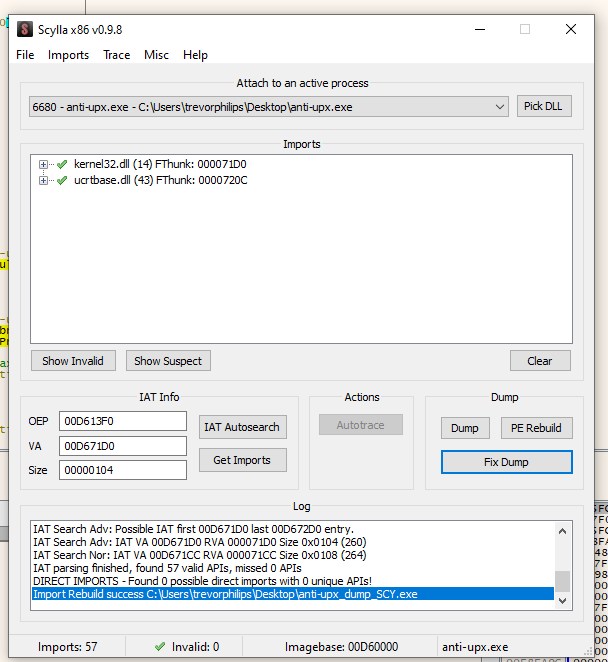

The steps for Scylla:

- IAT Autosearch

- Get Imports

- Fix Dump (Choose the dump.exe from OllyDump previously)

Next, decompile the dump executables and find string of “incorrect” or “flag” to get analyze the function that process the input.

Also to take note, there are more functions showing as it was resolved at the left side, indicating the executable is unpacked from the previous process.

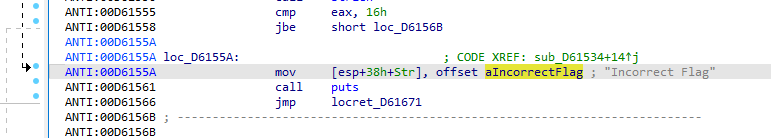

Here is the “Incorrect Flag” string, we can decompile this function and analyze the execution flow. Here is the decompiled code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

int __cdecl sub_D61534(char *Str)

{

bool v2; // al

char Str1[4]; // [esp+16h] [ebp-22h] BYREF

char v4; // [esp+1Ah] [ebp-1Eh]

char v5[4]; // [esp+1Bh] [ebp-1Dh] BYREF

int v6; // [esp+1Fh] [ebp-19h]

__int16 v7; // [esp+23h] [ebp-15h]

char Destination[4]; // [esp+25h] [ebp-13h] BYREF

int v9; // [esp+29h] [ebp-Fh]

__int16 v10; // [esp+2Dh] [ebp-Bh]

bool v11; // [esp+2Fh] [ebp-9h]

if ( strlen(Str) <= 0x15 || strlen(Str) > 0x16 )

return puts(aIncorrectFlag);

*(_DWORD *)Destination = 0;

v9 = 0;

v10 = 0;

*(_DWORD *)v5 = 0;

v6 = 0;

v7 = 0;

*(_DWORD *)Str1 = 0;

v4 = 0;

strncpy(Destination, Str, 9u);

HIBYTE(v10) = 0;

strncpy(v5, Str + 9, 9u);

HIBYTE(v7) = 0;

strncpy(Str1, Str + 18, 4u);

v4 = 0;

v2 = (unsigned __int8)sub_D61673(Destination) && (unsigned __int8)sub_D618F7(v5) && (unsigned __int8)sub_D6196B(Str1);

v11 = v2;

if ( !v2 )

return puts(aIncorrectFlag);

puts(aCongratsCorrec);

return sub_D62B10(aFlagS, (char)Str);

}

This function takes in string as arguments which then will check for its length, it should be containing 22 (0x16) character. Next, there are 3 strncpy with two 9 characters long and last one is 4 characters long. Later on, each substring will be process individually and return the result.

Here is the function sub_D61673:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

BOOL __cdecl sub_D61673(char *Str)

{

char v2[10]; // [esp+1Dh] [ebp-1Bh] BYREF

bool v3; // [esp+27h] [ebp-11h]

char *Str1; // [esp+28h] [ebp-10h]

int i; // [esp+2Ch] [ebp-Ch]

if ( strlen(Str) != 9 )

return 0;

for ( i = 0; i <= 8; ++i )

v2[i] = Str[8 - i];

v2[9] = 0;

Str1 = (char *)sub_D619E5(v2);

if ( !Str1 )

return 0;

v3 = strncmp(Str1, Str2, 9u) == 0;

free(Str1);

return v3;

}

From Str2 the value is -KCH-VGAN and reverse our way up, notice that another function call is use to proceed the input which is reversed and stored into v2. Checking into sub_D619E5, you will notice is a ROT13 transformation function. So to sum up the first substring transformation process, first reverse the string, then ROT13, finally check whether it matches with -KCH-VGAN.

Following the next substring process, sub_D618F7:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

BOOL __cdecl sub_D618F7(char *Str)

{

bool v2; // [esp+1Bh] [ebp-Dh]

char *Str1; // [esp+1Ch] [ebp-Ch]

if ( strlen(Str) != 9 )

return 0;

Str1 = sub_D61715((int)Str, 9u);

if ( !Str1 )

return 0;

v2 = strncmp(Str1, aVu5qnenlm1jf, 0xCu) == 0;

free(Str1);

return v2;

}

It is straight away a base64 string comparison, the base64 encoding implementation is in the function sub_D61715. Base64 decode Vu5qnenlm1jf is UNP4CK3R_

Finally, the last function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

bool __cdecl sub_D6196B(char *Str1)

{

char Str2[5]; // [esp+13h] [ebp-25h] BYREF

__time64_t Time; // [esp+18h] [ebp-20h] BYREF

char v4[4]; // [esp+24h] [ebp-14h]

int v5; // [esp+28h] [ebp-10h]

struct tm *v6; // [esp+2Ch] [ebp-Ch]

Time = time64(0);

v6 = localtime64(&Time);

v5 = v6->tm_year + 1900;

*(_DWORD *)v4 = v5 - 688;

sub_D62AC0(Str2, aD, v5 + 80);

return strncmp(Str1, Str2, 4u) == 0;

}

This function get the current system time with the time64 and subtract it with 688. So, this year is 2025, subtracting it with 688 gives us 1337

Here is the solution script:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

import base64

from datetime import datetime

# Part 1: Reverse and ROT13

def reverse_rot13(s):

return s[::-1].translate(str.maketrans(

'ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz',

'NOPQRSTUVWXYZABCDEFGHIJKLMnopqrstuvwxyzabcdefghijklm'

))

part1 = reverse_rot13("-KCH-VGAN") # Should be "ANTI-UPX-"

# Part 2: Base64 decode

def decode_base64(s):

return base64.b64decode(s).decode('utf-8')

part2 = decode_base64("VU5QNENLM1Jf") # Should be "UNP4CK3R_"

# Part 3: Current year minus 688

def get_year_part():

current_year = datetime.now().year

return str(current_year - 688)

part3 = get_year_part() # Should be "1337" (if the current year is 2025)

# Combine all parts to form the flag

print(part1+part2+part3)

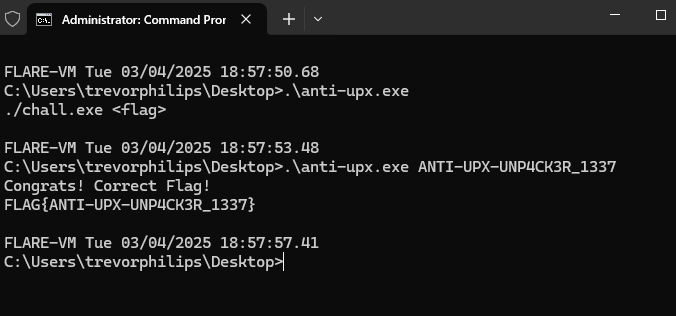

So, our input string to get the flag is ANTI-UPX-UNP4CK3R_1337

Flag: FLAG{ANTI-UPX-UNP4CK3R_1337}